aliases:

- Motion Profile

- Trapezoidal ProfileMotion Profiles

Success Criteria

- Configure a motion system with PID and FeedForward

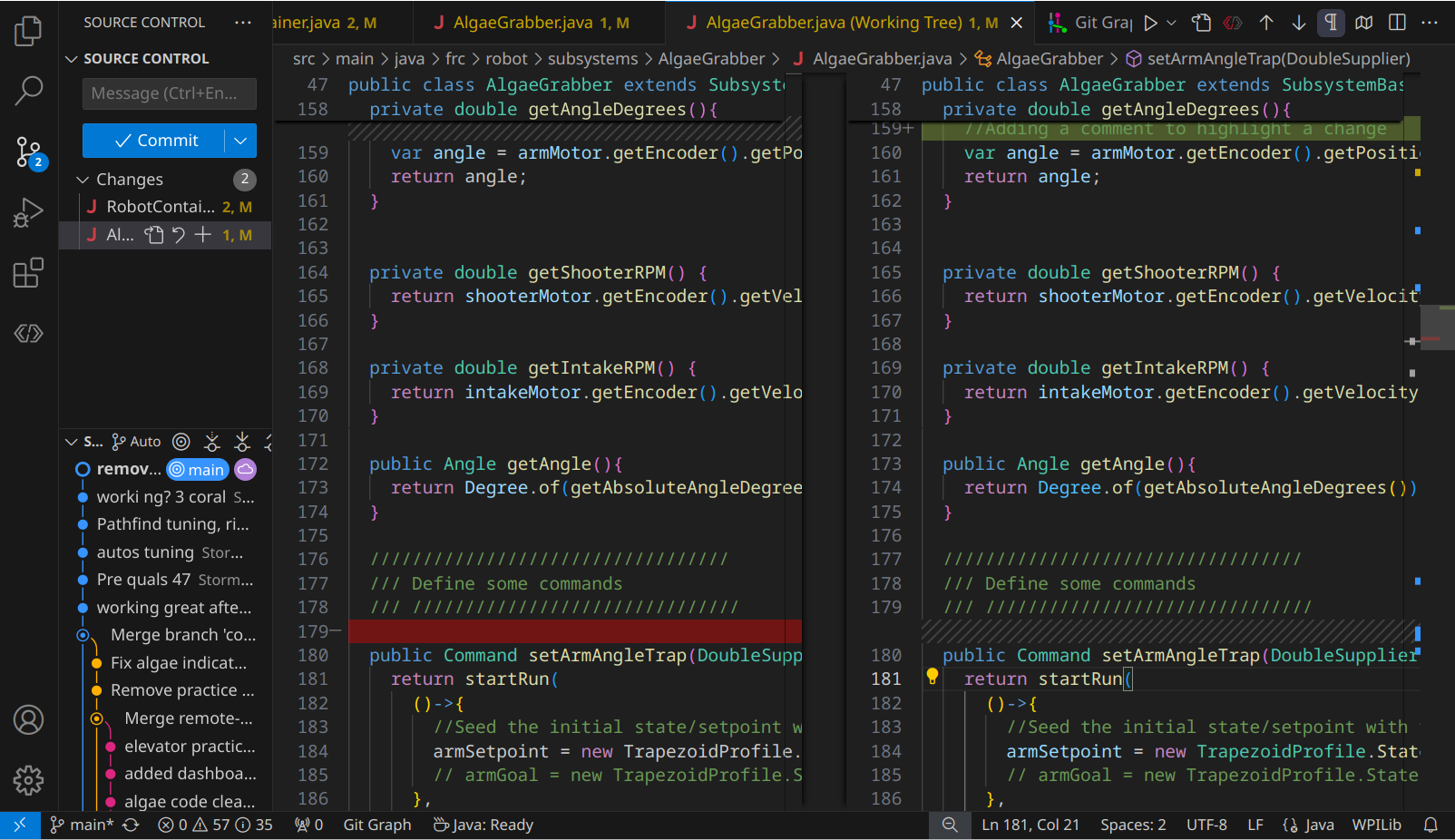

- Add a trapezoidal motion profile command (runs indefinitely)

- Create a decorated version with exit conditions on reaching the target

- Create a small auto sequence to cycle multiple points

- Create a set of buttons for different setpoints

Synopsis

Motion Profiling is the process of generating smooth, controlled motion. This is typically done using controlled, intermediate setpoints, consideration of the system's physical properties, and other imposed limitations.

In FRC our tooling generally utilizes a Trapazoidal profile, allowing us precise control of system position, maximum system speed, and acceleration applied to the system.

Benefits of Motion profiling

Motion Profiling resolves several problems that can come up with "simpler" control systems such as simple open loop or straight PID control.

The first comes from acknowledgement of the basic physics equation

The next relates to "tuning": The process of adjusting robot parameters to generate consistent motion. If you've gone through the PID tuning process, you probably remember one struggle: Your tuning works great until you move the setpoint a larger distance, at which point it wildly misbehaves, and the system acts erratically. This case is caused by sharp changes in system error, resulting in the PID generating a large output. Motion profiles instead change the setpoint at a controlled rate, ensuring a small system error keeping the PID in a much more stable state.

The extra complexity is worth it! Tuning a system using a Motion Profile is significantly less work than without it, since all the biggest pain points are eliminated. Your PID behaves better, with no overshoot or sharp outputs, and your system

How it works

For these purposes, we're going to discuss a "positional" control system, such as an Elevator or Arm .

Motion Profiles still apply to velocity control Rollers and Flywheels; In those cases, we ignore the position, smoothly accelerating to our target velocity. This means we only see half the benefit on those systems.

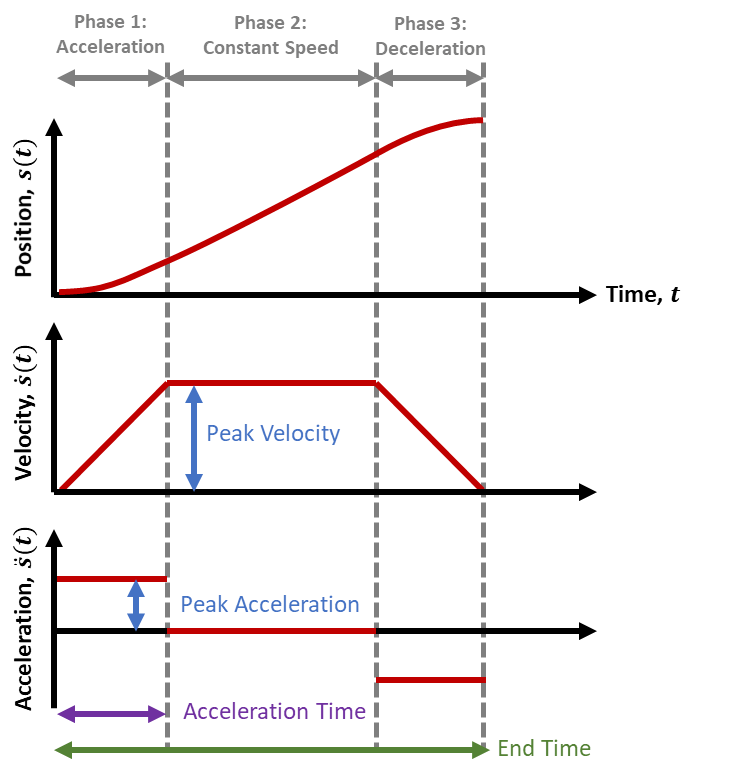

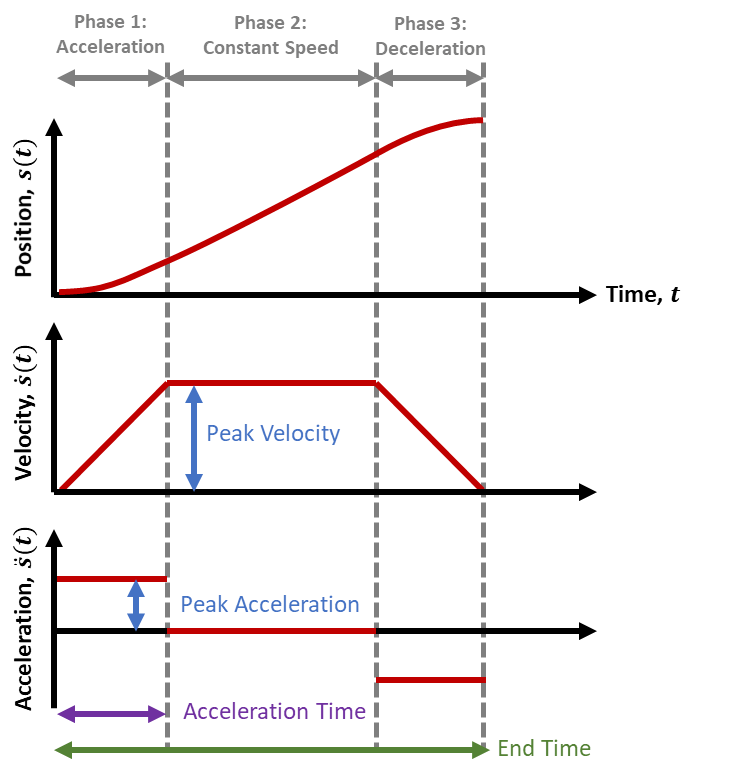

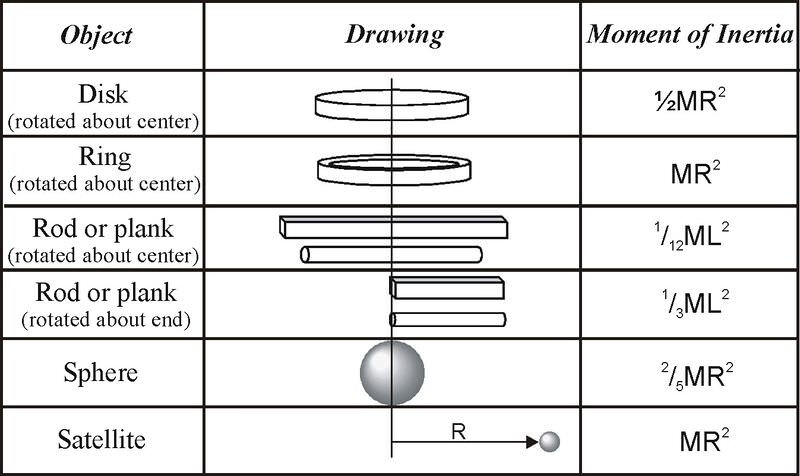

The system we typically use is a "Trapezoidal" profile, named after the shape of the velocity graph it generates.

This system has just two parameters:

- A maximum velocity

- a maximum acceleration.

By having these values set at values the physical system can achieve, our motion profile can split up one large motion into 3 segments.

- An acceleration step, where the motor is approaching the max speed

- Running at our max speed

- Decelerating on approach to the final position.

Because our Motion Profile is aware of our system capabilities, it can then constrain our setpoint changes to ones that that our system can actually achieve, generating a smooth motion without overshooting our final target (or goal).

Since we know how long it takes to accelerate and decelerate, and the max speed, we can also predict exactly how long the whole motion takes!

The entire motion looks just like this:

Finding Max Velocity

A theoretical maximum can be found by multiplying your maximum motor RPM by your gear reduction: It's very similar to configuring your encoder conversion factor, then hitting it with your maximum velocity.

In practice, you normally want to start by setting it slow, at something that you can visually track: Often ~1-2 seconds for a specific range of motion. This helps with testing, since you can see it work and mentally confirm whether it's what you expect.

As you improve and tune your system, you can simply then increase the maximum until your system feels unsafe, and then go back down a bit.

In many practical FRC systems, you may not hit the actual maximum speed of your system: Instead, the system well simply accelerate to the halfway point and then decelerate. This is normal, and simply means the system is constrained by the acceleration.

Finding Max Acceleration

The maximum acceleration effectively represents the actual force we're telling the motor to apply. It's easiest to understand at the extremes:

- When set to zero, your system will never have force applied; It won't move at all.

- When set to infinite, your system assumes it can reach to the max velocity instantly; This is effectively just applying as much force as your system is configured for.

However, in actual systems you want them to move, so zero is useless. And infinite is useful, but impractical: Thinking back to our equation,

This final form helps us clearly see we have a maximum: Our output force is is defined by the motor's max output and our system's mass, giving us a maximum constraint:

Note this is highly simplified: Actually calculating max acceleration this way on real-world systems is often non-trivial, and involves significantly more variables and equations than listed here. However, it's the concept that's important.

In practice, the easiest way to find acceleration is to simply start small increase the acceleration until the system moves how you want. If it starts making concerning noises or over-shooting, then you've gone too far, and you should back it off.

Revisiting the graph

With some background, there's a couple ways to visually interpret this graph:

- This graph always represents the generated profile, but also should reflect your actual position too! When configured correctly, the generated graph is always within our system's capability.

- The calculated "position" setpoint is generally what we feed to our system's PID output.

- The "acceleration" impacts the angle on our velocity trapezoid! At infinite, it's vertical, and at zero, it's horizontal.

Interactions with FeedForwards

Having a motion profile also enables inputs for FeedForwards, allowing even higher levels of precision on your expected outputs.

At the basic level, positional PIDs can be trivially configured with kG and kS, which only depend on values known on all systems. kG is constant or depends on position, and kS depends only on direction of motion.

However, the kV and kA gains both depend on not just on position, but also a known system acceleration and velocity targets.... which we haven't had with arbitrary setpoint jumps.

But now, we can plan our motion: Giving us velocity and acceleration targets. With the right feedforwards, we can now compute the moment-to-moment output for the entire motion in advance!

Interaction with PIDs

The most important part is that our error changes from one big setpoint jump to a lot of small, properly calculated ones.

Without a feed-forward, simply having a motion profile completely removes the big transitions and associated output spikes. This makes tuning simpler, less critical, and often allows for more aggressive PID gains without problems. However, many positional systems will usually still need an I term to accurately hit setpoints accurately without rapid oscillations from a high P term.

With a partial FeedForward (kG + kS) the Feed-Forward handles the base lifting, reducing the need of a PID to handle gravity. This leaves the PID left to handle the motion itself, and it can easily hit setpoint targets without an I term, barring weight changes (such as loaded game pieces)

With a full FeedForward, the error between commanded motion and actual motion will be extremely small, making the PID's impact almost completely irreverent. This makes the PID tuning extremely easy, and the gains can be tuned for precisely the expected disturbances you'll encounter, such as impacts or weight variation.

Note, that despite having theoretically minimal impact, you would still always want a PID to ensure the system gets back to position in cause of error.

Tuning Errors and Adjustments

Fortunately, with motion profiles you get a lot, with very little in the way of potential problems.

Most errors can be easily captured by looking at the position and velocity graph of a real system, and applying a bit of reasoning on what line isn't matching up.

- Overshooting the position setpoint at the end: This likely means your acceleration is too high, or your I gain is too large.

- The system is lagging behind the setpoints and the lines are diverting entirely. It then overshoots the setpoint: Your system cannot output enough power to meet your acceleration constraint. Make sure you have appropriate current limits, and/or lower the acceleration within the system capability.

- The system is lagging behind the setpoints so the lines are parallel but offset: This is typical when not using kA+kV, or when they're set too low. The difference is how long it takes the PID control to kick in and make up for what kA+kV should be generating for that motion.

- The motion is very jerky when travelling at the max speed: This usually means kV is too high, but can be kS being too high. Lowering kP may help as well.

- It starts really awful and smooths out: Likely kA is too high, although again kS and kP can influence this.

Implementing <system type here>

The full system and example code is part of the system descriptions:

The most effective way in general is using the WPILib ProfiledPIDController providing the simplest complete implementation.

This works as a straight upgrade to the standard PID configuration, but takes 2 additional parameters that grant huge performance gains and easier tuning.

ExampleElevator extends SubsystemBase{

SparkMax motor = new SparkMax(42,kBrushless);

//Configure reasonable profile constraints

private final TrapezoidProfile.Constraints constraints =

new TrapezoidProfile.Constraints(kMaxVelocity, kMaxAcceleration);

//Create a PID that obeys those constraints in it's motion

//Likely, you will have kI=0 and kD=0

//Note, the unit of our PID will need to be in Volts now.

private final ProfiledPIDController controller =

new ProfiledPIDController(kP, kI, kD, constraints, 0.02);

//Our feedforward object appropriate for our subsystem of choice

//When in doubt, set these to zero (equivilent to no feedforward)

//Will be calculated as part of our tuning.

private final ElevatorFeedforward feedforward =

new ElevatorFeedforward(kS, kG, kV);

//Lastly, we actually use our new

public Command setHeight(Supplier<Distance> position){

return run(

()->{

//Update our goal with any new targets

controller.setGoal(position.get().in(Inches));

//Calculate the voltage

voltage=

motor.setVoltage(

controller.calculate(motor.getEncoder().getPosition())

+ feedforward.calculate(controller.getSetpoint().velocity)

);

});

}

The big difference compared to our other, simpler PID is that we're using motor.setVoltage for this; This relates to the inclusion of FeedForwards which prefers volts for improved consistency as the battery drains.

While the PID itself doesn't care, since we're adding them together they do need to be the same unit.

If you already calculated your PID gains using motor.set() or

FeedForwards

Requires:

Motor Control

Success Criteria

- Create a velocity FF for a roller system that enables you to set the output in RPM

- Create a gravity FF for a elevator system that holds the system in place without resisting external movement

- Create a gravity FF for an arm system that holds the system in place without resisting external movement

Synopsis

Feedforwards model an expected motor output for a system to hit specific target values.

The easiest example is a motor roller. Let's say you want to run at ~3000 RPM. You know your motor has a top speed of ~6000 RPM at 100% output, so you'd correctly expect that driving the motor at 50% would get about 3000 RPM. This simple correlation is the essence of a feed-forward. The details are specific to the system at play.

Explanation

The WPILib docs have good fundamentals on feedforwards that is worth reading.

https://docs.wpilib.org/en/stable/docs/software/advanced-controls/controllers/feedforward.html

Tuning Parameters

Feed-forwards are specifically tuned to the system you're trying to operate, but helpfully fall into a few simple terms, and straightforward calculations. In many cases, the addition of one or two terms can be sufficient to improve and simplify control.

kS : Static constant

The simplest feedforward you'll encounter is the "static feed-forward". This term represents initial momentum, friction, and certain motor dynamics.

You can see this in systems by simply trying to move very slow. You'll often notice that the output doesn't move it until you hit a certain threshhold. That threshhold is approximately equal to kS.

The static feed-forward affects output according to the simple equation of

kG : Gravity constant

a kG value effectively represents the value needed for a system to negate gravity.

Elevators are the simpler case: You can generally imagine that since an elevator has a constant weight, it should take a constant amount of force to hold it up. This means the elevator Gravity gain is simply a constant value, affecting the output as

A more complex kG calculation is needed for pivot or arm system. You can get a good sense of this by grabbing a heavy book, and holding it at your side with your arm down. Then, rotate your arm outward, fully horizontal. Then, rotate your arm all the way upward. You'll probably notice that the book is much harder to hold steady when it's horizontal than up or down.

The same is true for these systems, where the force needed to counter gravity changes based on the angle of the system. To be precise, it's maximum at horizontal, zero when directly above or below the pivot. Mathematically, it follows the function

This form of the gravity constant affects the output according to

kV : Velocity constant

The velocity feed-forward represents the expected output to maintain a target velocity. This term accounts for physical effects like dynamic friction and air resistance, and a handful of

This is most easily visualized on systems with a velocity goal state. In that case,

In contrast, for positional control systems, knowing the desired system velocity is quite a challenge. In general, you won't know the target velocity unless you're using a Motion Profiles to to generate the instantaneous velocity target.

kA : Acceleration constant

The acceleration feed-forward largely negates a few inertial effects. It simply provides a boost to output to achieve the target velocity quicker.

like

The equations of FeedForward

Putting this all together, it's helpful to de-mystify the math happening behind the scenes.

The short form is just a re-clarification of the terms and their units

A roller system will often simply be

An elevator system will look similar:

Lastly, elevator systems differ only by the cosine term to scale kG.

Of course, the intent of a feed-forward is to model your mechanics to improve control. As your system increases in complexity, and demands for precision increase, optimal control might require additional complexity! A few common cases:

- If you have a pivot arm that extends, your kG won't be constant!

- Moving an empty system and one loaded with heavy objects might require different feed-forward models entirely.

- Long arms might be impacted by motion of systems they're mounted on, like elevators or the chassis itself! You can add that in and apply corrective forces right away.

Feed-forward vs feed-back

Since a feed-forward is prediction about how your system behaves, it works very well for fast, responsive control. However, it's not perfect; If something goes wrong, your feed-forward simply doesn't know about it, because it's not measuring what actually happens.

In contrast, feed-back controllers like a PID are designed to act on the error between a system's current state and target state, and make corrective actions based on the error. Without first encountering system error, it doesn't do anything.

The combination of a feed-forward along with a feed-back system is the power combo that provides robust, predictable motion.

FeedForward Code

WPILib has several classes that streamline the underlying math for common systems, although knowing the math still comes in handy! The docs explain them (and associated warnings) well.

https://docs.wpilib.org/en/stable/docs/software/advanced-controls/controllers/feedforward.html

Integrating in a robot project is as simple as crunching the numbers for your feed-forward and adding it to your motor value that you write every loop.

ExampleSystem extends SubsystemBase(){

SparkMax motor = new SparkMax(...)

// Declare our FF terms and our object to help us compute things.

double kS = 0.0;

double kG = 0.0;

double kV = 0.0;

double kA = 0.0;

ElevatorFeedforward feedforward = new ElevatorFeedforward(kS, kG, kV, kA);

ExampleSubsystem(){}

Command moveManual(double percentOutput){

return run(()->{

var output ;

//We don't have a motion profile or other velocity control

//Therefore, we can only assert that the velocity and accel are zero

output = percentOutput+feedforward.calculate(0,0);

// If we check the math, this feedforward.calculate() thus

// evaluates as simply kg;

// We can improve this by instead manually calculating a bit

// since we known the direction we want to move in

output = percentOutput + Math.signOf(percentOutput) + kG;

motor.set(output);

})

}

Command movePID(double targetPosition){

return run(()->{

//Same notes as moveManual's calculations

var feedforwardOutput = feedforward.calculate(0,0);

// When using the Spark closed loop control,

// we can pass the feed-forward directly to the onboard PID

motor

.getClosedLoopController()

.setReference(

targetPosition,

ControlType.kPosition,

ClosedLoopSlot.kSlot0,

feedforwardOutput,

ArbFFUnits.kPercentOut

);

//Note, the ArbFFUnits should match the units you calculated!

})

}

Command moveProfiled(double targetPosition){

// This is the only instance where we know all parameters to make

// full use of a feedforward.

// Check [[Motion Profiles]] for further reading

}

}

Rev released a new FeedForward config API that might allow advanced feed-forwards to be run directly on controller. Look into it and add examples!

https://codedocs.revrobotics.com/java/com/revrobotics/spark/config/feedforwardconfig

Finding Feed-Forward Gains

When tuning feed-forwards, it's helpful to recognize that values being too high will result in notable problems, but gains being too low generally result in lower performance.

Just remember that the lowest possible value is 0; Which is equivalent to not using that feed forward in the first place. Can only improve from there.

It's worth clarifying that the "units" of feedForward are usually provided in "volts", rather than "percent output". This allows FeedForwards to operate reliably in spite of changes of supply voltage, which can vary from 13 volts on a fresh battery to ~10 volts at the end of a match.

Percent output on the other hand is just how much of the available voltage to output; This makes it suboptimal for controlled calculations in this case.

Finding kS and kG

These two terms are defined at the boundary between "moving" and "not moving", and thus are closely intertwined. Or, in other words, they interfere with finding the other. So it's best to find them both at once.

It's easiest to find these with manual input, with your controller input scaled down to give you the most possible control.

Start by positioning your system so you have room to move both up and down. Then, hold the system perfectly steady, and increase output until it just barely moves upward. Record that value.

Hold the system stable again, and then decrease output until it just barely starts moving down. Again, record the value.

Thinking back to what each term represents, if a system starts moving up, then the provided input must be equal to

Helpfully, for systems where

For pivot/arm systems, this routine works as described if you can calculate kG at approximately horizontal. It cannot work if the pivot is vertical. If your system cannot be held horizontal, you may need to be creative, or do a bit of trig to account for your recorded

Importantly, this routine actually returns a kS that's often slightly too high, resulting in undesired oscillation. That's because we recorded a minimum that causes motion, rather than the maximum value that doesn't cause motion. Simply put, it's easier to find this way. So, we can just compensate by reducing the calculated kS slightly; Usually multiplying it by 0.9 works great.

Finding roller kV

Because this type of system system is also relatively linear and simple, finding it is pretty simple. We know that

We know

This means we can quickly assert that

Finding kV+Ka

Beyond roller kV, kA and kV values are tricky to identify with simple routines, and require Motion Profiles to take advantage of. As such, they're somewhat beyond the scope of this article.

The optimal option is using System Identification to calculate the system response to inputs over time. This can provide optimal, easily repeatable results. However, it involves a lot of setup, and potentially hazardous to your robot when done without caution.

The other option is to tune by hand; This is not especially challenging, and mostly involves a process of moving between goal states, watching graphs, and twiddling numbers. It usually looks like this:

- Identify two setpoints, away from hard stops but with sufficient range of motion you can hit target velocities.

- While cycling between setpoints, increase increase kV until the system generates velocities that match the target velocities. They'll generally lag behind during the acceleration phase.

- Then, increase kA until the acceleration shifts and the system perfectly tracks your profile.

- Increase profile constraints and and repeat until system performance is attained. Starting small and slow prevents damage to the mechanics of your system.

This process benefits from a relatively low P gain, which helps keep the system stable and near the intended setpoints, but running without a PID at all is actually very informative too.

Once your system is tuned, you'll probably want a relatively high P gain, now that you can assert the feed-forward is keeping your error close to zero, but be aware that this can result in slight kV errors resulting in a "jerky" motion. Lowering kV slightly below nominal can help resolve this.

Modelling changing systems

NEEDS TESTING We haven't had to do this much! Be mindful that this section may contain structural errors, or we may find better ways to approach these issues

When considering these systems, remember that they're linear systems: This helpful quirk means we can simply add the system responses together:

ElevatorFeedforward feedforward = new ElevatorFeedforward(kS, kG, kV, kA);

ElevatorFeedforrward ff_gamepiece = new ElevatorFeedforward(kS, kG, kV, kA);

//...

var output = feedforward.calculate(...) + ff_gamepiece.calculate(...)

This lets you respond to things such as a heavy game piece being loaded.

Modelling Complex Systems

As systems increase in complexity and precision requirements, you might need to do more advanced modelling, while keeping in mind the mathematical flexibility of adding and multiplying smaller feed-forward components together!

Here's some examples:

- If your arm extends, you can simply interpolate between a "fully retracted" feedforward and a "fully extended" ones; Thanks to the system linearity, this allows you to model the entire range of values quickly and easily.

- Arm motions can be impacted by the acceleration of a chassis or elevator; While gravity is a constant acceleration (and thus constant force), other non-constant accelerations can also be modeled as part of your feedforward and added to the base calculations.

Footnotes

Note, you might observe that the kCos output,

PID

tags:Requires

Commands

Encoder Basics

Success Criteria

- Create a PID system on a test bench

- Tune necessary PIDs using encoders

- Set a velocity using a PID

- Set a angular position using a PID

- Set a elevator position using a PID

- Plot the system's position, target, and error as you command it.

TODO

TODO:

Add some graphs

https://github.com/DylanHojnoski/obsidian-graphs

Write synopsis

https://docs.revrobotics.com/revlib/spark/closed-loop

Synopsis

A PID system is a Closed Loop Controller designed to reduce system error through a simple, efficient mathematical approach.

You may also appreciate Chapter 1 and 2 from controls-engineering-in-frc.pdf , which covers PIDs very well.

Definitions:

Before getting started, we need to identify a few things:

- A setpoint: This is the goal state of your system. This will have units in that target state, be it height, meters, rotations/second, or whatever you're trying to do.

- An output: This is often a motor actuator, and likely

- A measurement: The current state of your system from a sensor; It should have the same units as your Setpoint.

- Controller: The technical name for the logic that is controlling the motor output. In our case, it's a PID controller, although many types of controllers exist.

Deriving a PID Controller from scratch

To get an an intuitive understanding about PIDs and feedback loops, it can help to start from scratch, and kind of recreating it from the basic assumptions and simple code.

Let's start from the core concept of "I want this system to go to a position and stay there".

Initially, you might simply say "OK, if we're below the target position, go up. If we're above the target position, go down." This is a great starting point, with the following pseudo-code.

setpoint= 15 //your target position, in arbitrary units

sensor= 0 //Initial position

if(sensor < setpoint){ output = 1 }

else if(sensor > setpoint){ output = -1 }

motor.set(output)

However, you might see a problem. What happens when setpoint and sensor are equal?

If you responded with "It rapidly switches between full forward and full reverse", you would be correct. If you also thought "This sounds like it might damage things", then you'll understand why this controller is named a "Bang-bang" controller, due to the name of the noises it tends to make.

Your instinct for this might be to simply not go full power. Which doesn't solve the problem, but reduces it's negative impacts. But it also creates a new problem. Now it's going to oscillate at the setpoint (but less loudly), and it's also going to take longer to get there.

So, let's complicate this a bit. Let's take our previous bang-bang, but split the response into two different regions: Far away, and closer. This is easier if we introduce a new term: Error. Error just represents the difference between our setpoint and our sensor, simplifying the code and procedure. "Error" helpfully is a useful term, which we'll use a lot.

run(()->{

setpoint= 15 //your target position, in arbitrary units

sensor= 0 //read your sensor here

error = setpoint-sensor

if (error > 5){ output = -1 }

else if(error > 0){ output = -0.2 }

else if(error < 0){ output = 0.2 }

else if(error < -5){ output = 1 }

motor.set(output)

})

We've now slightly improved things; Now, we can expect more reasonable responses as we're close, and fast responses far away. But we still have the same problem; Those harsh transitions across each else if. Splitting up into more and more branches doesn't seem like it'll help. To resolve the problem, we'd need an infinite number of tiers, dependent on how far we are from our targets.

With a bit of math, we can do that! Our error term tells us how far we are, and the sign tells us what direction we need to go... so let's just scale that by some value. Since this is a constant value, and the resulting output is proportional to this term, let's call it kp: Our proportional constant.

run(()->{

setpoint= 15 //your target position, in arbitrary units

sensor= 0 //read your sensor here

kp = 0.1

error = setpoint-sensor

output = error*kp

motor.set(output)

)}

Now we have a better behaved algorithm! At a distance of 10, our output is 1. At 5, it's half. When on target, it's zero! It scales just how we want.

Try this on a real system, and adjust the kP until your motor reliably gets to your setpoint, where error is approximately zero.

In doing so, you might notice that you can still oscillate around your setpoint if your gains are too high. You'll also notice that as you get closer, your output drops to zero. This means, at some point you stop being able to get closer to your target.

This is easily seen on an elevator system. You know that gravity pulls the elevator down, requiring the motor to push it back up. For the sake of example, let's say an output of 0.2 holds it up. Using our previous kP of 0.1, a distance of 2 generates that output of 0.2. If the distance is 1, we only generate 0.1... which is not enough to hold it! Our system actually is only stable below where we want. What gives!

This general case is referred to as "standing error" ; Every loop through our PID fails to reduce the error to zero, which eventually settles on a constant value. So.... what if.... we just add that error up over time? We can then incorporate that error into our outputs. Let's do it.

setpoint= 15 //your target position, in arbitrary units

errorsum=0

kp = 0.1

ki = 0.001

run(()->{

sensor= 0 //read your sensor here

error = setpoint-sensor

errorsum += error

output = error*kp + errorsum*ki

motor.set(output)

}

The mathematical operation involved here is called integration, which is what this term is called. That's the "I" in PID.

In many practical FRC applications, this is probably as far as you need to go! P and PI controllers can do a lot of work, to suitable precision. This a a very flexible, powerful controller, and can get "pretty good" control over a lot of mechanisms.

This is probably a good time to read across the WPILib PID Controller page; This covers several useful features. Using this built-in PID, we can reduce our previous code to a nice formalized version that looks something like this.

PIDController pid = new PIDController(kP, kI, kD);

run(()->{

sensor = motor.getEncoder.getPosition();

motor.set(pid.calculate(sensor, setpoint))

})

A critical detail in good PID controllers is the iZone or ErrorZone. We can easily visualize what problem this is solving by just asking "What happens if we get a game piece stuck in our system"?

Well, we cannot get to our setpoint. So, our errorSum gets larger, and larger.... until our system is running full power into this obstacle. That's not great. Most of the time, something will break in this scenario.

So, the iZone allows you to constrain the amount of error the controller actually stores. It might be hard to visualize the specific numbers, but you can just work backward from the math. If output = errorsum*kI, then maxIDesiredTermOutput=iZone*kI. So iZone=maxIDesiredTermOutput/kI.

Lastly, what's the D in PID?

Well, it's less intuitive, but let's try. Have you seen the large spike in output when you change a setpoint? Give the output a plot, if you so desire. For now, let's just reason through a system using the previous example PI values, and a large setpoint change resulting in an error of 20.

Your PI controller is now outputting a value of 2.0 ; That's double full power! Your system will go full speed immediately with a sharp jolt, have a ton of momentum at the halfway point, and probably overshoot the final target. So, what we want to do is constrain the speed; We want it fast but not too fast. So, we want to reduce it according to how fast we're going.

Since we're focusing on error as our main term, let's look at the rate the error changes. When the error is changing fast we want to reduce the output. The difference is simply defined as error-previousError, so a similar strategy with gains gives us output+=kP*(error-previousError) .

This indeed gives us what we want: When the rate of change is high, the contribution is negative and large; Acting to reduce the total output, slowing the corrective action.

However, this term has another secret power, which disturbance rejection. Let's assume we're at a steady position, and the system is settled, and error=0. Now, let's bonk the system downward, giving us a sudden large, positive error. Suddenly nonzero-0 is positive, and the system generates a upward force. For this interaction, all components of the PID are working in tandem to get things back in place quickly.

Adding this back in, gives us the fundamental PID loop:

setpoint= 15 //your target position, in arbitrary units

errorsum=0

lastSensor=0

kp = 0.1

ki = 0.001

kd = 0.01

run(()->{

sensor= 0 //read your sensor here

error = setpoint-sensor

errorsum += error

errordelta = sensor-lastSensor

lastSensor=sensor

output = error*kp + errorsum*ki + errordelta*kd

motor.set(output)

}

Complete Java Example

Adding PID control to a system can vary slightly on system, but at the core it's pretty straightforward:

For controlling a simple positional system like an Elevator, it'd looks something like this

ExampleElevator extends SubsystemBase{

SparkMax motor = new SparkMax(42,kBrushless);

//Create a PID that obeys those constraints in it's motion

//Likely, you will have kI=0 and kD=0

//The unit of error will be in inches

//The P gain units should be percentoutput/distance

private final PIDController controller =

new PIDController(kP, kI, kD);

public Command setHeight(Supplier<Distance> position){

return run(

()->{

var output=controller.calculate(

motor.getEncoder().getPosition(),

position.in(Inches)

);

motor.set(output);

});

}

}

For a Roller system, we often want to control the rate, not the position: That's easy too!

ExampleElevator extends SubsystemBase{

SparkMax motor = new SparkMax(42,kBrushless);

//Create a PID that obeys those constraints in it's motion

//Likely, you will have kI=0 and kD=0

//The unit of error will be in RotationsPerMinute or

// RotationsPerSecond (whichever you prefer) to work with.

//The P gain units should be percentoutput/rate

private final PIDController controller =

new PIDController(kP, kI, kD);

//Lastly, we actually use our new

public Command setSpeed(Supplier<AngularVelocity> speed){

return run(

()->{

var output=controller.calculate(

motor.getEncoder().getVelocity(),

speed.in(RPS) //or RPM if your gains are adjusted with that

);

motor.set(output);

});

}

}

Looking carefully, we can see that the only thing we do is just change our units around, as well as the function calls to get the appropriate units.

Limitations of PIDs

OK, that's enough nice things. Understanding PIDs requires knowing when they work well, and when they don't, and when they actually cause problems.

- PIDs are reactive, not predictive. Note our key term is "error" ; PIDs only act when the system is already not where you want it, and must be far enough away that the generated math can create corrective action.

- Large setpoint changes break the math. When you change a setpoint, the P output gets really big, really fast, resulting in an output spike. When the PID is acting to correct it, the errorSum for the I term is building up, and cannot decrease until it's on the other side of the setpoint. This almost always results in overshoot, and is a pain to resolve.

- Oscillation: PIDs inherently generate oscillations unless tuned perfectly. Sometimes big, sometimes small.

- D term instability: D terms are notoriously quirky. Large D terms and velocity spikes can result in bouncy, jostly motion towards setpoints, and can result in harsh, very rapid oscillations around the zero, particularly when systems have significant Mechanical Backlash.

- PIDS vs Hard stops: Most systems have one or more Hard Stops, which present a problem to the I term output. This requires some consideration on how your encoders are initialized, as well as your setpoints.

- Tuning is either simple....or very time consuming.

- Only works on "Linear" systems: Meaning, systems where the system's current state does not impact how the system responds to a given output. Arms are an example of a non-linear system, and to a given output very differently when up and horizontally. These cannot be properly controlled by just a PID.

So, how do you make the best use of PIDs?

- Reduce the range of your setpoint changes. There's a few ways to go about it, but the easiest are clamping changes, Slew Rate Limiting and Motion Profiles . With such constraints, your error is always small, so you can tune more aggressively for that range.

- Utilize FeedForwards to create the basic action; Feed-forwards create the "expected output" to your motions, reducing the resulting error significantly. This means your PID can be tuned to act sharply on disturbances and unplanned events, which is what they're designed for.

In other words: This is an error correction mechanism. By reducing or controlling the initial error a PID would act on, you can greatly simplify the PID's affect on your system, usually making it easier to get better motions. Using a PID as the "primary action" for a system might work, but tends to generate unexpected challenges.

Tuning

Tuning describes the process of dialing in our "gain values"; In our examples, we named these kP, kI, and kD. These values don't change the process of our PID, but it changes how it responds.

There's actually several "formal process" for tuning PIDs; However, in practice these often are more complicated and aggressive than we really want. You can read about them if you'd like PID Tuning via Classical Methods

In practice though, the typical PID tuning process is more straightforward, but finicky.

- Define a small range you want to work with: This will be a subset of

- Create a plot of your setpoint, current state/measurements, and system output. Basic Telemetry is usually good enough here.

- Starting at low values, increase the P term until your system starts to oscillate near the goal state. Reduce the P term until it doesn't. Since you can easily

- Add an I term, and increase the value until your system gets to the goal state with minimal overshoot. Often I terms should start very small; Often around 1%-10% of your P term. Remember, this term is summed every loop; So it can build up very quickly when the error is large.

- If you're tuning a shooter system, get it to target speed, and feed in a game piece; Increase the D term until you maintain the RPM to an effective extent.

Rev controllers by default implement a velocity filter, making it nearly impossible to detect rapid changes in system velocity. This in turn makes it nearly impossible to tune a D-term.

#todo Document how to remove these filters

Be aware that poorly tuned PIDs might have very unexpected, uncontrolled motions, especially when making big setpoint changes.

They can jolt unexpectedly, breaking chains and gearboxes. They can overshoot, slamming into endstops and breaking frames. They'll often oscillate shaking loose cables, straps, and stressing your robot.

Always err on the side of making initial gains smaller than expected, and focus on safety when tuning.

Remember that for PID systems the setpoint determines motor output; If the bot is disabled, and then re-enabled, the bot will actuate to the setpoint!

Make sure that your bot handles re-enabling gracefully; Often the best approach is to re-initialize the setpoint to the bot's current position, and reset the PID controller to clear the I-term's error sum.

Streamlining tuning the proper way

In seasons past, a majority of our programming time was just fiddling with PID values to get the bot behaviour how we want it. This really sucks. Instead, there's more practical routines to avoid the need for precision PID tuning.

- Create a plot of your setpoint, current state/measurements, and system output. Basic Telemetry is usually good enough here.

- Add a FeedForward : It doesn't have to be perfect, but having a basic model of your system massively reduces the error, and significantly reduces time spent fixing PID tuning. This is essential for Arms; The FeedForward can easily handle the non-linear aspects that the PID struggles with.

- In cases where game pieces contribute significantly to the system load, account for it with your FeedForward: Have two different sets of FeedForward values for the loaded and unloaded states

- Use Motion Profiles: A Trapezoidal profile is optimal and remarkably straightforward. This prevents many edge cases on PIDs such as sharp transitions and overshoot. It provides very controlled, rapid motion.

- Alternatively, reduce setpoint changes through use of a Ramp Rate or Slew Rate Limiting. This winds up being as much or more work than Motion Profiles with worse results, but can be easier to retrofit in existing code.

- An even easier and less effective option is simply Clamp clamp the setpoint within a small range around the current state. This provides a max error, but does not eliminate the sharp transitions.

- Set a very small ClosedLoopRampRate; Just enough to prevent high-frequency oscillations, which will tend to occur when the setpoint is at rest, especially against Hard Stops or if Backlash is involved. This is just a Slew Rate Limiter being run on the motor controller against the output.

From here, the actual PID values are likely to barely matter, making tuning extremely straightforward:

- Increase the P term until you're on target through motions and not oscillating sharply at rest

- Find a sensible output value that fixes static/long term disturbances (change in weight, friction, etc). Calculate the target iZone to a sensible output just above what's needed to fix those.

- Start with I term of zero; Increase the I term if your system starts lagging during some long motions, or if it sometimes struggles to reach setpoint during

- If your system is expected to maintain it's state through predictable disturbances (such as maintaining shooter RPM when launching a game piece), test the system against those disturbances, and increase the D term as needed. You may need to decrease the P term slightly to prevent oscillations when doing this.

- Watch your plots. A well tuned system should

- Quickly approach the target goal state

- Avoid overshooting the target

- Settle on a stable output value

- Recover to the target goal state (quickly if needed)

TODO

- Discontinuity + setpoint wrappping for PIDs + absolute sensors

SuperStructure Rollers

tags:

aliases:

- Rollers

- RollerRequires:

Motor Control

Recommends:

FeedForwards

PID

Success Criteria

- Create a Roller serving as a simple intake

- Create Commands for loading, ejecting, and stopping

- Create a default command that stops the subsystem

- Bind the load and eject operations to a joystick

Optional Bonus criteria:

- Configure the Roller to use RPM instead of setPower

- Add a FeedForward and basic PID

- Confirm the roller roughly maintains the target RPM when intaking/ejecting

Synopsis

A Roller system is a simple actuator type: A single motor output mechanically connected to a rotating shaft. Objects contacting the shaft forms the useful motion of a Roller system. This can also extended with additional shafts, belts, or gearing to adjust the contact range.

Despite the simplicity, Rollers are very flexible and useful systems in FRC. When paired with clever mechanical design, Rollers can accomplish a wide variety of game tasks, empower other system types, and serve as the foundation of more complex systems.

Common use cases

On their own, rollers can be designed to serve a few functions

- Fixed position Intakes, responsible for pulling objects into a robot

- Simple scoring mechanisms for ejecting a game piece from the bot

- Simple launchers game pieces from the robot at higher speeds

- As motion systems to move game pieces through the bot

- As a simple feeder system for allowing or blocking game piece motion within the bot.

Rollers of this nature are very common on Kitbot designs, owing to the mechanical simplicity and robustness of these systems.

For more complex bots, Roller systems are usually modified with extra mechanical features or actuated. These include

- A Flywheel system, which provides more accurate launching of game pieces through precision control and increased momentum

- As Indexers/Feeder/Passthrough, providing precision control of game pieces through a bot.

- As actuated Intakes, often with rollers attached to Arms or linkages

These documents discuss the special considerations for improving Rollers in those applications.

Implementing a Roller

Analysis

In keeping with a Roller being a simple system, they're simple to implement: You've already done this with Motor Control.

To integrate a Roller system into your bot code, there's simply a few additional considerations:

- The function of your roller: This determines the role and name of your system. Like all subsystems, you want the name to be reflective of it's task, and unique to help clarify discussion around the system.

- Level of control needed: Rollers often start simple and grow in complexity, which is generally preferred. But, sometimes you can tell that your system will get complicated, and it's worth planning for.

- The base tasks this system performs.

- sometimes a Roller system will serve multiple roles: Usually, it's good to recognize this early to facilitate naming and configuration.

These are effectively what we see in Robot Design Analysis , but especially pertinent for Roller systems. Since your system will likely have multiple rollers, naming them "Rollers" is probably a bad idea. Assigning good names to the roller system and the actions it performs will make your code easier to follow.

Rollers generally will have a few simple actions, mostly setting a power and direction, with appropriate names depending on the intent of the action:

- Intake rollers usually have "intake", "eject", and "stop" which apply a fixed motor power. Larger game pieces might also have a "hold", which applies a lower power to keep things from shifting or falling out.

- Rollers in a Launcher role will usually have "shoot" and "stop", and rarely need to do much else.

- Rollers serving as a "feeder" will usually alternate between the "launcher" and "intake" roles; So it'll need appropriate actions for both.

Code Structure

Appropriately, a useful, minimal roller system is very straightforward, and done previously in Motor Control. But this time let's clean up names.

public Launcher extends SubsystemBase{

SparkMax motor = new SparkMax(42,kBrushless);

Launcher(){

//Normal constructor tasks

//Configure motor: See Motor Control for example code

//Set the default command; In this case, just power down the roller

setDefaultCommand(setPower(0)); //By default, stop

}

public Command setPower(double power){

// Note use of a command that requires the subsystem by default

// and does not exit

return run(()->motor.set(power));

}

public Command launchNear(){

return setPower(0.5);

}

public Command launchFar(){

return setPower(1);

}

}

For most Roller systems, you'll want to keep a similar style of code structure: By having a setPower(...) command Factory, you can quickly build out your other verbs with minimal hassle. This also allows easier testing, in case you have to do something like attach a Joystick to figure out the exact right power for a particular task.

In general, representing actions using named command factories with no arguments is preferable, and will provide the cleanest code base. The alternatives such as making programmers remember the right number, or feeding constants into setPower will result in much more syntax and likelyhood of errors.

Having dedicated command factories also provides a cleaner step into modifying logic for certain actions. Sometimes later you'll need to convert a simple task into a short sequence, and this convention allows that to be done easily.

Boosting Roller capability

Without straying too far from a "simple" subsystem, there's still a bit we can do to resolve problems, prevent damage, or streamline our code.

FeedForwards and PIDs for consistent, error free motion

Sometimes with Roller systems, you'll notice that the power needed to move a game piece often provides undesirable effects when initially contacting a game piece. Or, that sometimes a game piece loads wrong, jams, and the normal power setting won't move it.

This is a classic case where error correcting methods like PIDs shine! By switching your roller from a "set power" configuration to a "set rotational speed" one, you can have your rollers run at a consistent speed, adjusting the power necessary to keep things moving.

Notably though, PIDs for rollers are very annoying to dial in, owing to the fact that they behave very differently when loaded and unloaded, and even more so when they need to actually resolve an error condition like a jam!

The use of a FeedForward aids this significantly: Feedforward values for rollers are extremely easy to calculate, and can model the roller in an unloaded, normal state. This allows you to operate "unloaded", with nearly zero error. When operating with very low error, your PID will be much easier to deal with, and much more forgiving to larger values.

You can then tune the P gain of your PID such that your system behaves as expected when loaded with your game piece. If the FF+P alone won't resolve a jamming issue, but more power will, you can add an I gain until that helps push things through.

Sensors + Automated actions

Some Roller actions can be improved through the use of Sensors, which generally detect the game piece directly. This helps rollers know when they can stop and end sequences, or select one of two actions to perform.

However, it is possible (although sometimes a bit tricky) to read the motor controller's built in sensors: Often the Current draw and encoder velocity. When attempting this, it's recommended to use Trigger with a Debounce operation, which provides a much cleaner signal than directly reading these

You can also read the controller position too! Sometimes this requires a physical reference (effectively Homing a game piece), which allows you to assert the precise game piece location in the bot.

In other cases you can make assertions solely from relative motion: Such as asserting if the roller rotated 5 times, it's no longer physically possible to still be holding a game piece, so it's successfully ejected.

Default Commands handling states

Many Roller systems, particularly intakes will wind up with in one of two states: Loaded or Unloaded, with each requiring a separate conditional action.

The defaultCommand of a Roller system is a great place to use this, using the Command utility ConditionalCommand (akaeither ). A common case is to apply a "hold" operation when a game piece is loaded, but stop rollers if not.

Implemented this way, you can usually avoid more complex State Machines, and streamline a great deal of code within other sequences interacting with your roller.

Power Constraints + Current Limiting

Some Roller systems will pull objects in, where the object hits a hard stop. This is most common on intakes. In all cases, you want to constrain the power such that nothing gets damaged when the roller pulls a game piece in and stalls.

Beyond that, in some cases you can set the current very low, and replace explicit hold() actions and sensors with just this lower output current. You simply run the intake normally, letting the motor controller apply an appropriate output current.

This is not common, but can be useful to streamline some bots, especially with drivers that simply want to hold the intake button to hold a game piece.

Fault Detection

Should jams be possible in your roller system, encoder velocity and output current can be useful references, when combined with the consideration that

When a "jam" occurs, you can typicaly note

- A high commanded power

- A high output current

- A low velocity

//Current detection

new Trigger(()->motor.getAppliedOutput()>=.7 && motor.getOutputCurrent()>4).debounce(0.2);

//Speed Detection

new Trigger(()->motor.getAppliedOutput()>=.7 && motor.getEncoder().getVelocity()<300).debounce(0.2);

However, care should be taken to ensure that these do not also catch the spin up time for motors! When a motor transitions from rest to high speed, it also generates significant current, a low speed, and high commanded output.

Debouncing the trigger not only helps clean up the output signal, but for many simple Roller systems, they spin up quickly enough that the debounce time can simply be set higher than the spin up duration.

Superstructure Indexer

tags:

- stub

aliases:

- Indexer

- Passthrough

- FeederSynopsis

Superstructure component that adds additional control axes between intakes and scoring mechanisms. In practice, indexers often temporarily act as part of those systems at different points in time, as well performing it's own specialized tasks.

Common when handling multiple game pieces for storage and alignment, game pieces require re-orientation, adjustment or temporary storage, and for flywheel systems which need to isolate game piece motion from spinup.

Success Criteria

- ???

Code Considerations

Setting up an indexer is often a challenging process. It will naturally inherit several design goals and challenges from the systems it's connected to. This means it will often have a more complex API than most systems, often adopting notation from the connected systems.

The Indexer is often sensitive to hardware design quirks and changes from those adjacent systems, which can change their behavior, and thus the interfacing code.

Additionally, game piece handoffs can be mechanically complex, and imperfect. Often Indexers absorb special handling and fault detection, or at least bring such issues to light. Nominally, any such quirks are identified and hardware solutions implemented, or additional sensing is provided to facilitate code resolutions.

Sensing

Indexers typically require some specific information about the system state, and tend to be a place where some sort of sensor ends up as a core operational component. The exact type and placement can vary by archtype, but often involve

- Break beam sensors: These provide a non-contact, robust way to check game piece

- Current/speed sensing: Many game pieces can be felt by the

Indexer Archtypes

Superstructure Shooter

A shooter is simply a flywheel and supporting infrastructure for making game pieces fly from a robot

Success Criteria

Typically a "shooter" consists of

- a SuperStructure Flywheel to serve as a mechanical means to maintain momentum

- A Superstructure Indexer to time shots and ensure the shooter is at the indended speed

- A targeting system, often using Odometry or Vision

- A trajectory evaluation to control target RPM. This can be fixed targets, Lookup Tables, or more complex trajectory calculations

SuperStructure Intake

tags:

- stub

aliases:

- IntakeRequires:

SuperStructure Rollers

Sensing Basics

Recommends:

State Machines

Requires as needed:

SuperStructure Rollers

SuperStructure Elevator

SuperStructure Arm

Success Criteria

- Create an "over the bumper" intake system

- Add a controller button to engage the intake process. It must retract when released

- The button must automatically stop and retract the intake when a game piece is retracted

Synopsis

Intake complexity can range from very simple rollers that capture a game piece, to complex actuated systems intertwined with other scoring mechanisms.

A common "over the bumper" intake archetype is a deployed system that

- Actuates outward past the frame perimeter

- Engages rollers to intake game piece

- Retracts with the game piece upon completion of a game piece

The speed of deployment and retraction both impact cycle times, forming a critical competitive aspect of the bot.

The automatic detection and retraction provide cycle advantages (streamlining the driver experience), but also prevent fouls and damage due to the collisions on the deployed mechanism.

Intakes often are a Compound Subsystem , and come with several quirks for structuring and control

Intakes: Taming the unknown

The major practical difference between intakes and other "subsystems" is their routine interaction with unknowns. Intake arms might extend into walls, intake rollers might get pressed into a loading station, and everything is approaching game pieces in a variety of speeds and states. Every FRC intake is different, but this one aspect is consistent.

Good mechanical design goes a long way to handling unknowns, but programming is affected too. Programming a robust intake demands identifying and resolving ways that these interactions can go wrong, and resolving them in a way that leaves the robot in an operational state (and preferably, with a game piece). Sometimes this is resolved in code, and sometimes requires hardware or design tweaks. Intakes tend to have more physical iterations than many other parts of the robot.

Detection + Sensing

For most intakes, you want a clear confirmation that the intake process is Done and a game piece is loaded. This typically means reviewing the mechanical design, and identifying what, if any, sensing methods will work reliably to identify successful intake.

Common approaches are

- Break beams / Range finders like LaserCan : Since these sensors are non-contact, they provide a easy to use, and relatively safe way to interact with game pieces with little design overhead.

- A backplate with a switch/button: This requires special mechanical design, but gives a simple boolean state to indicate successful loading. This typically only works with intakes that interact with a back-stop, but can be made to work with other mechanisms that can actuate a switch when objects are in a known position

- Current Detection: This is a common option for intakes that pull in directly into a backstop, particularly for rigid game pieces. Like other places where current detection is used, it's either trivial + very effective, or ineffective + extremely challenging, depending on the design and interactions.

- Speed/Stall Detection: Like above but measuring roller speed rather than motor current.

A good understanding of Sensing Basics , and familiarity with our other sensors available will go a long way to making a robust intake.

Robot + Game Piece Safety

When intaking objects, many things can go wrong with. Here's a quick list of considerations:

- A game piece can be oriented wrong, jamming the intake.

- A game piece can be loaded from weird angles or during unexpected motions, jamming the intake

- A game piece can be loaded at the edge of the intake, binding against mechanical supports

- A game piece load can be interrupted by drivers, leaving the intake in a "default command" state while half-loaded

- A game piece can be damaged, loading in incorrectly or binding

- A game piece can be stretched/deformed inside the bot or intake

- A game piece can be smaller/larger than originally expected, causing various effects

- The game piece can be damaged due to excess force when stalled/jammed

- The game piece can be damaged due to initial contact with rollers at a high speed

- The intake can be extended past frame perimeter, and then slam into a wall

- The intake can be extend past the frame perimeter into a wall.

- The rollers can jam against an intake pressed against a wall

- The rollers+game piece can force other systems into unexpected angles due to wall/floor/loading station interactions

- Intakes can fling past the robot perimeter during collisions, colliding with other robots (collecting fouls or snagging wires)

Murphy's law applies! If anything can go wrong, it will. When testing, you might be tempted to assume errors are a one-off, but instead record them and try to replicate errors as part of your testing routine. It's easier to fix at home than it is in the middle of a competition.

When coding, pay close attention to

- Expected mechanism currents: Make sure that your intake is operating with reasonable current limits, and set high enough to work quickly, but low enough to prevent harm when something goes wrong.

- Intake Default Commands: Ideally, the code for your intake should ensure the system ends up in a stable, safe resting location.

- The expected and actual positions: In some cases, if there's a large mismatch between expected positions and the current one, you might infer there's a wall/object in the way and halt loading, or apply a different routine.

- Command conditions: Make sure that your start/stop conditions work reliably under a variety of conditions, and not just the "values when testing". You might need to increase them or add additional states in which sensor values are handled differently or ignored.

Fault Management

A good intake doesn't need to perfectly load a game piece in every scenario, but it does need to have a way to recover so you can resume the match. Let's look at a couple approaches

Load it anyway

The optimal result, of course, is successfully resolving the fault and loading the game piece. Several fault conditions can be resolved through a more complex routine. A couple common ones are

- Stop + restart the intake (with motor coast mode). This works surprisingly well, as it lets the game piece settle, slip away from obstructions, and then another intake attempt might successfully complete the load operation.

- Reverse + restart the intake. A more complex (and finicky) option, but with the same effect. This an help alleviate many types of jamming, stretching, squishing, and errant game piece modes, as well as re-seat intake wheels.

- Re-orient + restart: This can come up if there's mechanical quirks, such as known collision or positional errors that can result in binding (like snagging on a bumper). Moving your system a bit might fix this, allowing a successful intake

A good load routine might need support from your mechanical teams to fix some edge cases. Get them involved!

Stall/Incomplete load

If we can't fix it, let's not break it: This is a fault mitigation tactic, intended to preserve game piece and robot safety, and allow the robot to continue a match.

The most important part of this is to facilitate the drivers: They need an Eject button, that when held tries to clear a game piece from the system, putting it outside the frame perimeter. A good eject button might be a simple "roller goes backwards", but also might have more complex logic (positioning a system a specific way first) or even controlling other subsystems (such as feeders, indexers, or shooters).

Historically, a good Eject button solves a huge amount of problems, with drivers quickly identifying various error cases, and resolving with a quick tap. Often drivers can tap eject to implement "load it anyway" solution, helping prove it on the field before it's programmed as a real solution.

Irrecoverable jam

The big oof 💀. When this happens, your robot is basically out of commission on the field, or your drivers are slamming it against a wall to knock things loose.

In this case, you should be aiming to identify, replicate, and resolve the root cause. It's very likely that this requires mechanical teams to assist.

If the jam is not able to be mechanically prevented, then Programming's job is to resolve the intake process to make it impossible, or at least convert it to a temporary stall.

Making A Solid Intake

Within the vast possibility space of the intake you'll handle, there's a few good practices

- Test early, test often, capture a lot of errors.

- Revise the hardware, then revise the software: Fix the software only as needed to keep things working. Don't spend the time keeping junked intake designs limping along, unless needed for further testing.

- Closed loop: Several fault conditions can be avoided by using a velocity PID and feed-forwards to generate a slower, more consistent initial interaction with game pieces, and automatically apply more power in fault condition.

- Operate at the edge cases: Do not baby the intake, and do your best to generate repeatable fault conditions to inform the design.

- Operate in motion: Feeding the intake on a stationary chassis tends to feed differently than a mobile chassis and stationary game piece, or a mobile chassis + Mobile Game Piece.

Intakes + Other Subsystems

Interactions

Generally, intakes are not one "system", but often actuated to deploy it beyond the frame perimeter, or line it up with intake positions. These are often done using Arms or Elevators. In some cases, it's a deployable linkage using motors or Pnuematic Solenoids .

Intakes often also interact with gamepiece management systems, usually an Indexer/Passthrough that helps move the game piece through a scoring mechanism. In some systems, the intake is the scoring mechanism.

Naming

Regardless of the system setup, good Subsystem design remains, and the "Intake" name tends to be given to the end effector (usually Rollers) contacting the game piece, with intake actuators being named appropriately (like IntakeArm or IntakeElevator)

Code structure and control

PhotonVision Basics

tags:

- stubGoals

Interact with the PhotoVision UI and basic code structures

Success Criteria

- Connect to the WebUI

- Set up a camera

- Set up AprilTag Target

- Read target position via NT

Port Forwarding

This allows you to access PhotonVision via the roborio USB port.

This can be useful when debugging at competitions

https://docs.photonvision.org/en/latest/docs/quick-start/networking.html

PhotonVision Bringup

tags:

- stubSuccess Criteria

- Configure the PV networking

- Configure the PV hardware

- Set up a camera

- Create a Vision code class

- Configure PV class to communicate with the hardware

PhotonVision Odometry

tags:

- stubSuccess Criteria

- Set up a pipeline to identify april tags

- Configure camera position relative to robot center

- Set up a

PhotonVision Object Detection

tags:

- stubSuccess Criteria

- Add a Object detection pipeline

- Detect a game piece using color detection

- if available, detect it using a ML object model

Other tooling:

Basic Telemetry

tags:

aliases:

- NetworkTablesGoals

Understand how to efficiently communicate to and from a robot for diagnostics and control

Success Criteria

- Print a notable event using the RioLog

- Find your logged event using DriverStation

- Plot some sensor data (such as an encoder reading), and view it on Glass/Elastic

- Create a subfolder containing several subsystem data points.

As a telemetry task, success is thus open ended, and should just be part of your development process; The actual feature can be anything, but a few examples we've seen before are

Why you care about good telemetry

By definition, a program runs exactly as you the code was written to run. Most notably, this does not strictly mean the code runs as it was intended to.

When looking at a robot, there's a bunch of factors that can have be set in ways that were not anticipated, resulting in unexpected behavior.

Telemetry helps you see the bot as the bot sees itself, making it much easier to bridge the gap between what it's doing and what it should be doing.

Printing + Logging

Simply printing information to a terminal is often the easiest form of telemetry to write, but rarely the easiest one to use. Because all print operations go through the same output interface, the more information you print, the harder it is to manage.

This approach is best used for low-frequency information, especially if you care about quickly accessing the record over time. It's best used for marking notable changes in the system: Completion of tasks, critical events, or errors that pop up. Because of this, it's highly associated with "logging".

The methods to print are attached to the particular print channels

//System.out is the normal output channel

System.out.println("string here"); //Print a string

System.out.println(764.3); //you can print numbers, variables, and many other objects

//There's also other methods to handle complex formatting....

//But we aren't too interested in these in general.

System.out.printf("Value of thing: %n \n", 12);

A typical way this would be used would be something like this:

public ExampleSubsystem{

boolean isAGamePieceLoaded=false;

boolean wasAGamePieceLoadedLastCycle=false;

public Command load(){

//Some operation to load a game piece and run set the loaded state

return runOnce(()->isAGamePieceLoaded=true);

}

public void periodic(){

if(isAGamePieceLoaded==true && wasAGamePieceLoadedLastCycle==false){

System.out.print("Game piece now loaded!");

}

if(isAGamePieceLoaded==false && wasAGamePieceLoadedLastCycle==true){

System.out.print("Game piece no longer loaded");

}

wasAGamePieceLoadedLastCycle=isAGamePieceLoaded

}

}

Rather than spamming "GAME PIECE LOADED" 50 times a second for however long a game piece is in the bot, this pattern cleanly captures the changes when a piece is loaded or unloaded.

In a more typical Command based robot , you could put print statements like this in the end() operation of your command, making it even easier and cleaner.

The typical interface for reading print statements is the RioLog: You can access this via the Command Pallet (CTRL+Shift+P) by just typing > WPILIB: Start Riolog. You may need to connect to the robot first.

These print statements also show up in the DriverStation logs viewer, making it easier to pair your printed events with other driver-station and match events.

NetworkTables

Data in our other telemetry applications uses the NetworkTables interface, with the typical easy access mode being the SmartDashboard api. This uses a "key" or name for the data, along with the value. There's a couple function names for different data types you can interact with

// Put information into the table

SmartDashboard.putNumber("key",0); // Any numerical types like int or float

SmartDashboard.putString("key","value");

SmartDashboard.putBoolean("key",false);

SmartDashboard.putData("key",field2d); //Many built-in WPILIB classes have special support for publishing

You can also "get" values from the dashboard, which is useful for on-robot networking with devices like Limelight, PhotonVision, or for certain remote interactions and non-volatile storage.

Note, that since it's possible you could request a key that doesn't exist, all these functions require a "default" value; If the value you're looking for is missing, it'll just give you the provided default.

SmartDashboard.getNumber("key",0);

SmartDashboard.getString("key","not found");

SmartDashboard.getBoolean("key",false);

Networktables also supports hierarchies using the "/" seperator: This allows you to separate things nicely, and the telemetry tools will let you interface with groups of values.

SmartDashboard.putNumber("SystemA/angle",0);

SmartDashboard.putNumber("SystemA/height",0);

SmartDashboard.putNumber("SystemA/distance",0);

SmartDashboard.putNumber("SystemB/angle",0);

While not critical, it is also helpful to recognize that within their appropriate heirarchy, keys are displayed in alphabetical order! Naming things can thus be helpful to organizing and grouping data.

Good Organization -> Faster debugging

As you can imagine, with multiple people each trying to get robot diagnostics, this can get very cluttered. There's a few good ways to make good use of Glass for rapid diagnostics:

- Group your keys using

group/key. All items with the samegroup/value get put into the same subfolder, and easier to track. Often subsystem names make a great group pairing, but if you're tracking something specific, making a new group can help. - Label keys with units: a key called

angleis best when written asangle degree; This ensures you and others don't confuse it withangle rad. - Once you have your grouping and units, add more values! Especially when you have multiple values that should be the same. One of the most frequent ways for a system to go wrong is when two values differ, but shouldn't.

A good case study is an arm: You would have

- An absolute encoder angle

- the relative encoder angle

- The target angle

- motor output

And you would likely have a lot of other systems going on. So, for the arm you would want to organize things something like this

SmartDashboard.putNumber("arm/enc Abs(deg)",absEncoder.getAngle());

SmartDashboard.putNumber("arm/enc Rel(deg)",encoder.getAngle());

SmartDashboard.putNumber("arm/target(deg)",targetAngle);

SmartDashboard.putNumber("arm/output(%)",motor.getAppliedOutput());

A good sanity check is to think "if someone else were to read this, could they figure it out without digging in the code". If the answer is no, add a bit more info.

Glass

Glass is our preferred telemetry interface as programmers: It offers great flexibility, easy tracking of many potential outputs, and is relatively easy to use.

Glass does not natively "log" data that it handles though; This makes it great for realtime diagnostics, but is not a great logging solution for tracking data mid-match.

This is a great intro to how to get started with Glass:

https://docs.wpilib.org/en/stable/docs/software/dashboards/glass/index.html

For the most part, you'll be interacting with the NetworkTables block, and adding visual widgets using Plot and the NetworkTables menu item.

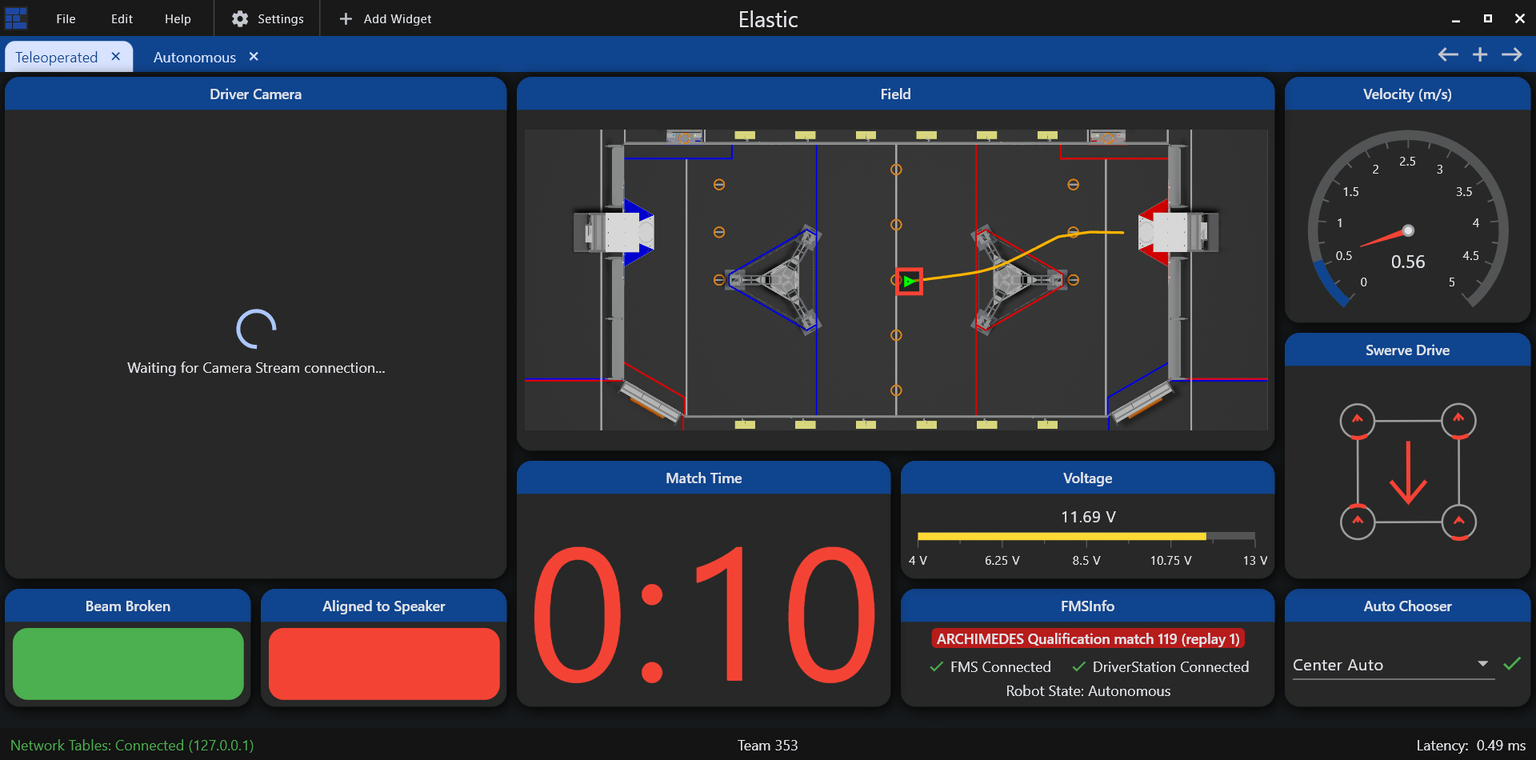

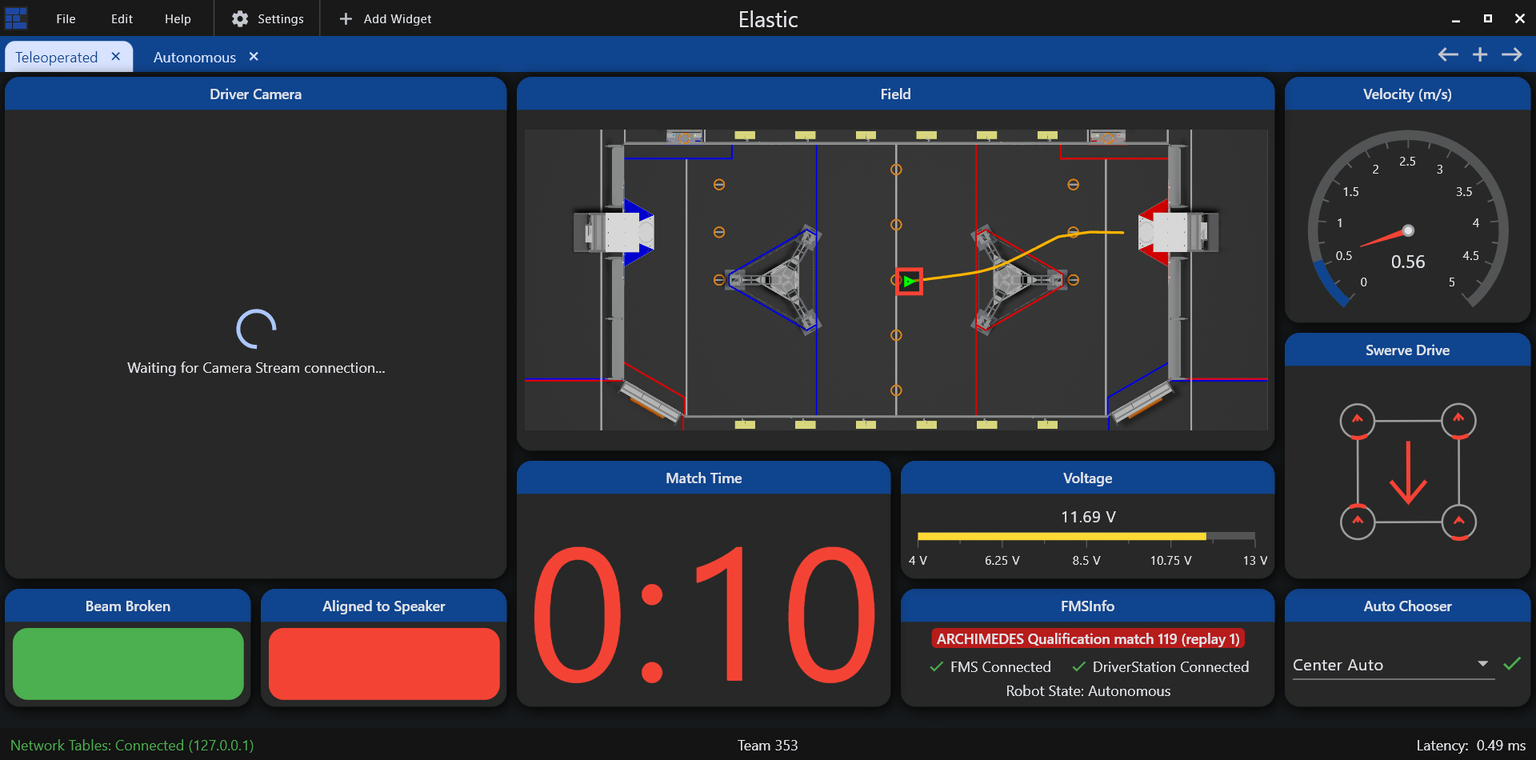

Elastic

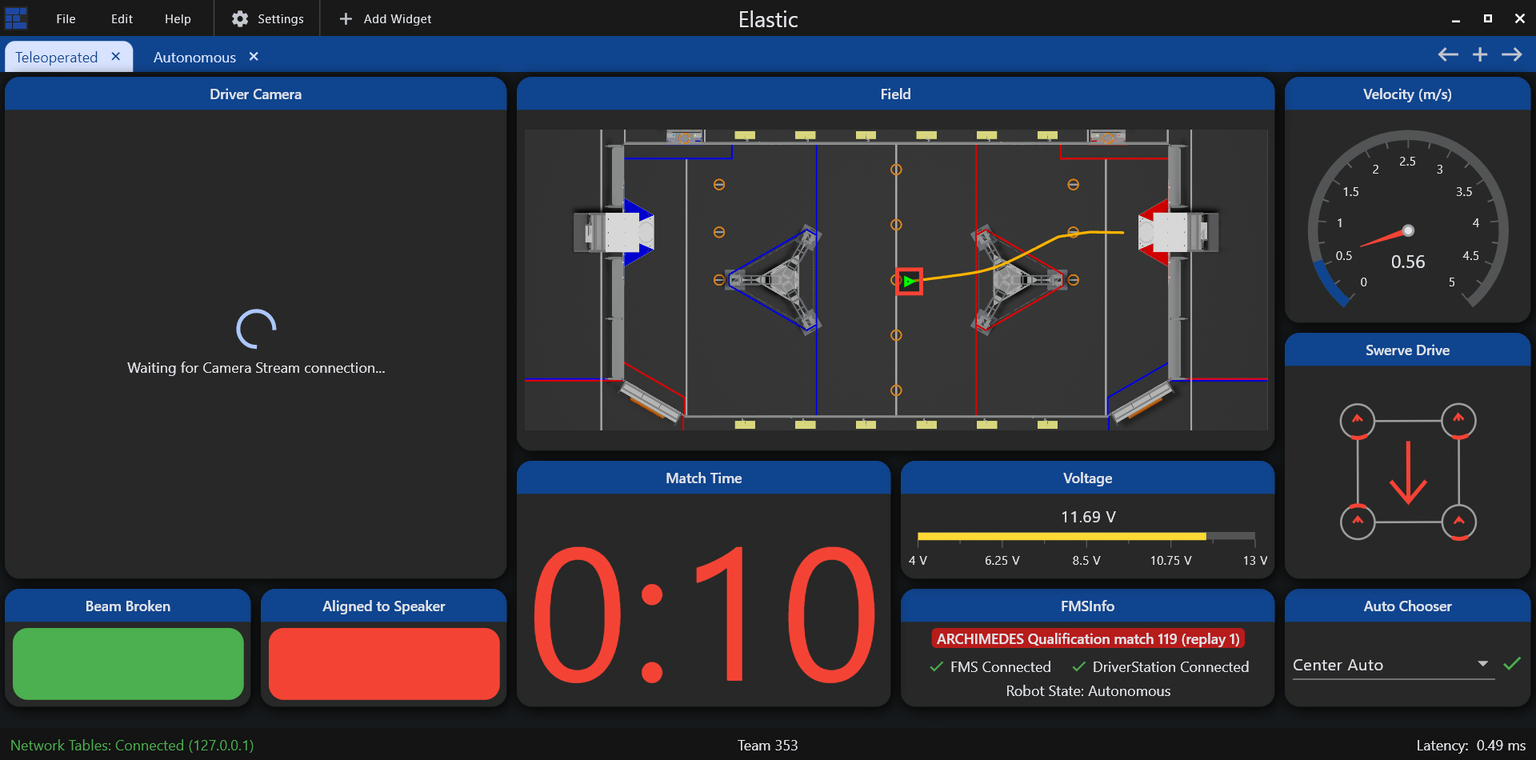

Elastic is a telemetry interface oriented more for drivers, but can be useful for programming and other diagnostics. Elastic excels at providing a flexible UI with good at-a-glance visuals for various numbers and directions.

Detailed docs are available here:

https://frc-elastic.gitbook.io/docs

As a driver tool, it's good practice to set up your drivers with a screen according to their preferences, and then make sure to keep it uncluttered. You can go to Edit -> Lock Layout to prevent unexpected changes.

For programming utility, open a new tab, and add widgets and items.

Plotting Data

Mechanism2d

tags:

- stubSuccess Criteria

- Create a basic Arm or Elevator motion system

- Create a Mechanism 2D representation of the control angle

- Create additional visual flair on mechanism to help indicate mechanism context

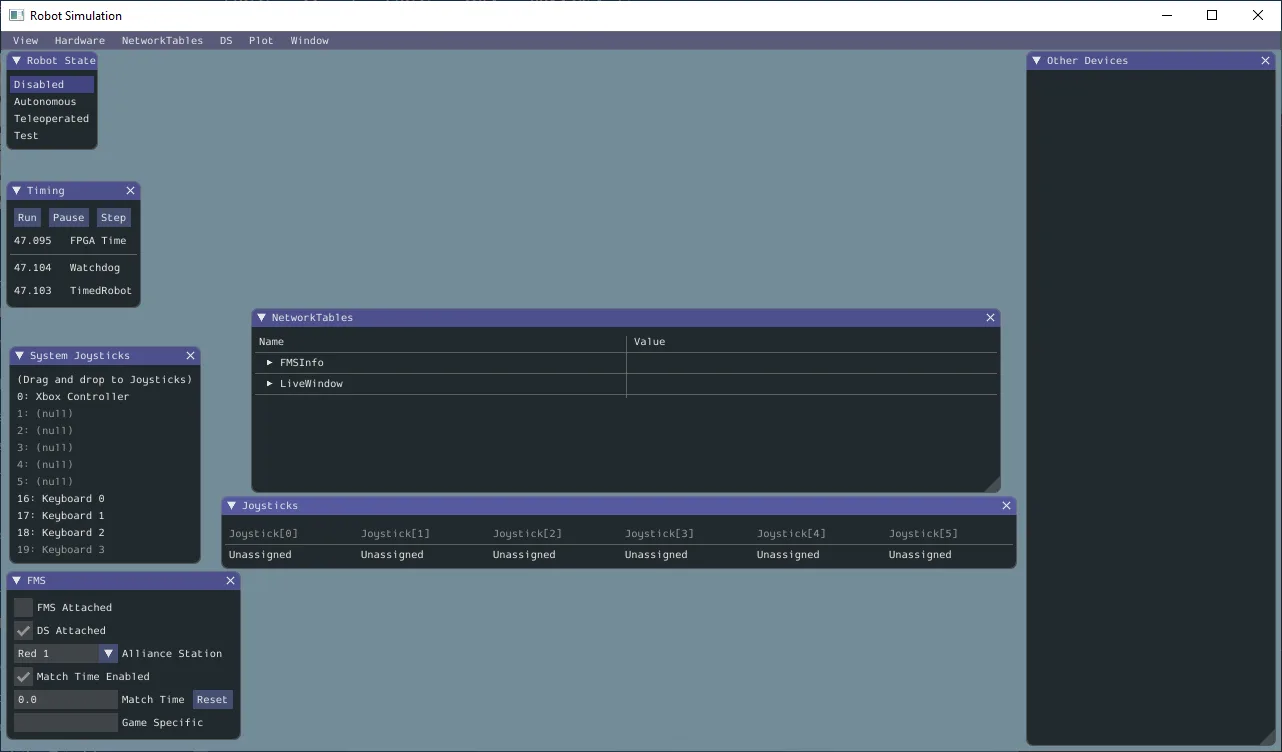

Physics Simulation

Success Criteria

- Create a standard Arm or Elevator

- Model the system as a Mechanism2D

- Create a Physics model class

- Configure the physics model

- Tune the model to react in a sensible way. It does not need to match a real world model

Brief rundown of some code

AdvantageKit

Success Criteria

- ??? Do we need or want this here?

- Need to find a way to actually use it efficiently in beneficial way

Goals

- Understand how to set up Advantagekit

Basic Odometry+Telemetry

aliases:

- Field2d

- Field OdometrySynopsis

Success Criteria

- Create a Widget on a dashboard to show the field

- Populate the Field with your robot, and one or more targets

- Utilize the Field to help develop a "useful feature" displayed on the Field

As a telemetry task, success is thus open ended, and should just be part of your development process; The actual feature can be anything, but a few examples we've seen before are

- showing which of several targets your code has deemed best, and react to it

- a path your robot is following, and where the bot is while following it

- The current Vision targets and where your bot is when seeing them

- A field position used as an adjustable target

- The projected path for a selected auto

- Inidcate proximity or zones "zones" for performing a task, such as the acceptable range for a shooting task or intaking process.

Odometry Fundamentals